My Fujifilm X-Pro2 Review: Why This Camera Still Matters in 2026

I’ve always been drawn to cameras that feel like companions rather than gadgets, and that’s why the Fujifilm X-Pro2 has become one of my favourite walk around cameras. Compact, tactile, and beautifully intuitive, it never gets in the way of "seeing" (even if I think I don't “see”, I just point at what I find interesting and noteworthy), which, for me, is the heart of photography.

There’s plenty of online talk and hype about the X-Pro2, and has been ever since it's release: its strengths, its quirks, whether it’s “still good” in a world of constant upgrades. I want to add my own view to that conversation, not as a spec sheet but as someone who takes the camera out and notices what it feels like to use day after day.

What struck me first about the X-Pro2 was its presence in the hand. Compared to my Canon cameras, it's compact without feeling small, solid without feeling heavy, and blessedly free of the menu-maze that plagues too many modern cameras. The rangefinder-style body and tactile dials make changing settings feel like a conversation rather than a chore: shutter speed, ISO, aperture all right there where you can touch them. This simplicity isn’t nostalgia, it’s clarity, functionality, and it matters.

Connected to that clarity is the imagery. The X-Pro2’s 24 megapixel APS-C X-Trans CMOS III sensor has a subtle and pleasing way of rendering tones that I find very satisfying. The files feel open yet detailed, colours feel alive yet grounded. Even before you start thinking about colour profiles or presets, the base imagery has a sort of honest gravity to it, the kind of look that makes everyday moments feel photographable. It this the "Fujifilm look"?

For me, the perfect partner in this is the "classic" Fujifilm 35 mm f/1.4 lens. This lens has a character that goes beyond sharpness charts or autofocus speed. Wide open, it delivers a soft fall-off and a gentle bokeh quality that feels both intimate and expressive. Details separate from backgrounds in a way that’s not aggressive, but suggestive, enough to attract the eye without shouting for attention.

There’s a texture to images made with this pairing that I really enjoy. Not dramatic, not engineered to impress, but somehow quietly distinctive. Maybe that’s why this camera and lens combination works so well for street, travel, and everyday photography. It lets me see what’s in front of me without imposing itself. I can wander through a market, sit by a café, walk in nature, or navigate crowded streets and let the world accumulate naturally in the frame.

One thing I often see discussed on Reddit, in Fujifilm forums and review threads is whether the X-Pro2 is “worth it” in 2026. From a purely specifications standpoint, it lacks things newer models have adopted, like in-body image stabilisation, for example. The battery life isn’t spectacular compared to modern rivals either. But those trade-offs feel intrinsic to its personality, not failures. This camera never pretended to be a video machine or a tech demo. It’s a seeing machine. And I've enjoyed far older cameras than the X-Pro2. So yes, it is still worth it.

I don’t use the X-Pro2 because it has the newest processor or the fastest autofocus. I use it because it makes me look not just at what’s easy to capture, but at what feels interesting, familiar, uncomfortable, or fleeting. A good camera shouldn’t always make your life easier, but it should make your seeing richer, to be a bit philosophical. The X-Pro2 does that for me.

Paired with the 35 mm f/1.4, it becomes more than a tool. It becomes something like a window into how and why I notice the world around me. There are cameras that can do more, or faster, or more feature-packed. But there are few that make me want to lift them again, quietly, thoughtfully, and just look.

Inside the car - on accumulation, personal space, and quiet traces of life

I’ve been photographing the interiors of people’s cars every now and then. First, I thought is was because of boredom, but the habit seems to return every now and then. What keeps drawing me back isn’t the objects themselves, but the feeling that these spaces are somehow unintentionally revealing. Cars seem to collect fragments of life in a way that feels different from homes or workplaces. Less permanent maybe, at least meant to be, and less planned, and thus a bit more honest.

Receipts, bottles and/or cans, old clothing, tangled cables, hand sanitiser, rackets. None of these things are remarkable on their own, yet together they form something that shows a life in motion. I started wondering why this happens. Why do cars, of all places, become sites of accumulation? And what does that accumulation say about the people who inhabit them?

In environmental psychology, personal spaces are often understood as extensions of the self. Researchers like Irwin Altman (1975) and later Russell Belk (1988) have written about how people use spaces and objects to establish identity, comfort, and control. Bedrooms, desks, and offices are classic examples, and I understand this. Cars, however, I feel occupy a strange middle ground. They are private spaces moving through public environments, intimate and somewhat controlled, but never fully settled.

Some studies describe cars as “mobile territories.” (Brown et al., 2005) We spend long stretches of time in them, often alone, and they become places where habits form. Objects are left not because they are meaningful in themselves, but because they are close at hand when life happens.After running errands, during transitions between A and B or one obligation and the next. Over time, these objects become quiet markers of routine and presence, and often left in the car, they inhabit that space.

There is also research suggesting that people are less motivated to organise transitional spaces than fixed ones. Unlike a home, a car is not meant to feel complete. It’s said to be provisional by nature (Sheller, 2004). That provisional quality seems to invite accumulation without intention. I see this as a kind of soft neglect that isn’t careless so much as human.

What interests me as a photographer is that these interiors feel like snapshots of snapshots. They are already composed by daily life, by movement, by distraction, by repetition. When I photograph them, I’m not arranging or interpreting so much as noticing what has already been left behind. At the same time, I’m aware that any meaning I see in these spaces is not universal. Research on visual perception and interpretation reminds us that images are always read through personal context. Each viewer brings their own memories, experiences, and associations. What feels mundane or empty to one person may feel intimate or charged to another.

The same is true for these car interiors. They are not objective records of identity. They are invitations. Someone else might see clutter where I see meaning, or randomness where I see rhythmicity.

Cars, in this sense, feel like extensions of our homes not because they are orderly or expressive, but because they carry traces of living without performance. They show what we don’t bother to edit. And photography, at least the kind that interests me, often begins exactly there — in spaces where life leaves marks without trying to say anything at all.

References

Altman, I. (1975). The environment and social behavior: privacy, personal space, territory, and crowding.

Belk, R. W. (1988). Extended self in consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(2).

Brown, G., Lawrence, T. B., & Robinson, S. L. (2005). Territoriality in organizations. Academy of management review, 30(3), 577-594.

Sheller, M. (2004). Automotive emotions: Feeling the car. Theory, culture & society, 21(4-5), 221-242.

Why Your Photos Feel Flat (And Why That’s Not Really the Problem)

I don’t know if my photos feel flat. I didn't think about this before I read it online.

Some of them probably do. Others don’t. What I've noticed more often is that photographs taken close together in time, sometimes even of similar, or the exact same things, can feel very different when I look at them later. One seems to hold my attention, while another, doesn’t really ask me to stay. It's not about the technical level. Perfectly nailed focus and composition, or out of focus and blurry, that's not what decides it.

When people describe photos as “flat,” they usually mean something like this, even if the word itself isn’t very precise. It sounds like a technical, or dramatic diagnosis (flat-line kind), but it rarely is. Most photographs that feel flat are exposed correctly, reasonably composed, and pleasant enough to look at. They aren’t wrong. They’re just...quiet...in some way.

So instead of asking why photos feel flat, I’ve started asking a slightly different question: why do some images hold attention, while others let it drift away?

The difference, I think, has less to do with drama or subject matter and more to do with decisiveness. Images that feel alive tend to make a small but clear demand on the viewer. They suggest where to look first. Not forever, just initially. They establish a kind of visual gravity, a sense that something in the frame matters more than the rest, even if it’s not immediately obvious why.

Photographs that feel flat often hesitate at that moment. Attention is spread evenly across the frame, with no element quite willing to speak. Everything is included, nothing is emphasised, and the image ends up being visually polite in some way. The eye enters, wanders without resistance, and eventually leaves. Not because the photograph is bad, but because it never really decided what it wanted to say visually.

This has very little to do with shallow depth of field or strong contrast, even though those tools can sometimes create emphasis. What’s really at stake is hierarchy. When a photograph commits to one relationship over others, like one tension, one alignment, one point of friction, it becomes easier for the viewer to enter it. When it doesn’t, the burden of interpretation falls entirely on the viewer, and most people won’t carry it for very long. I'm like that as well. Principle of least effort.

The same idea applies to depth. When images are described as flat, the word usually isn’t pointing at space so much as it’s pointing at relationships. A photograph can have plenty of physical depth and still feel inert if the elements within it lack interaction. Foreground, subject, and background might all be present, but if they merely coexist rather than push against each other, the image feels more like a collection of objects than a situation.

Depth, in this sense, comes from interaction rather than blur. Overlap, obstruction, framing, tension—these things create the feeling that parts of the image are aware of each other. Without that awareness, the photograph might remains visually shallow, no matter how technically accomplished it is.

Light plays a similar role. Not dramatic light, or “good” light in the usual sense, but light that describes form. Light that explains transitions, reveals volume, or subtly favors one area of the frame over another helps the image make a choice. When light is evenly distributed and non-committal, it often contributes to that sense of flatness—not because it’s wrong, but because it refuses to emphasize anything in particular.

What complicates all of this is meaning. It’s tempting to believe that photographs feel alive when they depict something meaningful, and flat when they don’t. But meaning, on its own, doesn’t guarantee engagement. A photograph can be about something important and still feel visually empty, just as a photograph with no obvious subject or story can feel strangely compelling.

Meaning usually arrives through structure rather than replacing it. If an image doesn’t give the viewer a way in, if it doesn’t guide attention or establish relationships, the meaning remains abstract, external to the photograph itself. The camera doesn’t know what matters conceptually, at least not yet, maybe in the future. It only responds to what is emphasised visually.

At the same time, meaning is never fixed. And this is what I find key here. Every photograph is read differently by every person who encounters it. Each viewer brings their own context, shaped by past experiences, memories, expectations, and even their sense of where they are in life. Something that feels mundane or flat to one person can quietly resonate with another. Images don’t contain meaning so much as they invite it, and the invitation is always interpreted differently.

That’s why I don’t think “flatness” is a final verdict. It’s a description of how an image lands for a particular viewer at a particular moment. And it’s also why I take photographs that are meaningful to me, even when I know they won’t speak the same way to everyone else, maybe no one else. My own context shapes what I notice, how I frame it, what I’m willing to exclude, and what I choose to emphasise. Those decisions, at least the visible ones, are what give a photograph its structure in the first place.

When a photograph feels flat to me, I try not to see it as a failure. I see it as feedback. It usually means I didn’t commit strongly enough, didn’t allow one relationship to dominate, or didn’t clearly decide what the image was asking the viewer to notice. I have noticed that this also correlates with levels of stress and expectations. Much like with life in general, usually slowing down helps. That’s not a technical problem. It’s a perceptual one.

And perception, unlike equipment or circumstances, is something that can be practiced. Not by forcing meaning into photographs, but by learning to notice more clearly what feels worth showing.

Handball photography - finding meaning in motion

Handball Photography: Finding Meaning in Motion

Handball is a game that allows little time for reflection. It unfolds in short, intense sequences of speed and contact, played out in indoor arenas where the light is rarely ideal and the rhythm of the game leaves little space for hesitation. To photograph it is to work slightly behind the action, always aware that the decisive moment has either just passed or is about to arrive, and that your task lies somewhere in that narrow space between the two. That space is not a limitation, but part of the medium, and for me, part of the charm.

Canon 1D X Mark III + Canon EF 200mm f/2.0L IS USM, 1/1600, f2.0, ISO3200

As with much of sports photography, the subject is not only the sport itself. What matters just as much is attention, or the ability to recognise when a routine movement, repeated dozens of times in a match, begins to carry weight and meaning. The challenge lies less in reacting quickly than in observing carefully, a challenge I find difficult. The great Peter Read Miller once spoke about the importance of photographing between moments, of looking beyond the obvious peak of action to what precedes it and what follows. Handball lends itself naturally to this approach. The expected images are always present: the airborne jump shot, the physical exchanges along the six-metre line etc. They describe the game clearly, but they rarely explain it fully.

Canon 1D X Mark III + Canon EF 200mm f/2.0L IS USM, 1/1600, f2.0, ISO3200

More often, it is the quieter images that remain, at least for me. A brief exchange of looks between players, a moment of thinking, a glance at the scoreboard, held a fraction of a second too long. A defender recognising, almost reluctantly, that they are late. These moments do not announce themselves, they cannot be forced, and they vary in each individual game. They depend on patience and on a willingness to let the game reveal itself rather than trying to extract images from it. The challenge for me is to rise above the obvious images, and find these moments in between.

From a technical perspective, conditions under which handball is photographed are not idea. Indoor arenas offer uneven lighting, mixed colour temperatures, and backgrounds crowded with advertising boards. There is no ideal light to wait for, only a set of constraints that must be worked within. In this context, technique becomes less about optimisation and more about consistency. Fast shutter speeds, never below 1/1000s, are necessary to contain the movement, often at the cost of light. Wide apertures help separate players from their surroundings, but depth of field becomes unforgiving. Not all shots are in focus with apertures ranging from f1.4-f2.0. High ISO, usually between ISO3200-6400, is unavoidable, and noise becomes part of the image’s texture rather than something to be eliminated entirely. Minor exposure compromises, grain, and edge blur are not signs of failure, but traces of the conditions in which the photograph was made. Luckily, the Canon 1D X Mark III excels at both autofocus and noise control.

Canon 1D X Mark III + Canon EF 200mm f/2.0L IS USM, 1/1600, f2.0, ISO3200

What matters more than technical refinement is anticipation. In handball, reacting is almost always too late. The game has a structure that reveals itself over time: players cutting along familiar lines, signalling their intentions through subtle shifts in posture, and goalkeepers committing to decisions long before the shot is released. The better this language is understood, the less the photographer depends on reflex and the more they can position themselves where the play is about to unfold. This familiarity with the game creates a sense of time, even within its speed. It allows the camera to be ready before the moment arrives, rather than chasing it as it disappears, because that chase is one that, at least I, will never win.

Canon 1D X Mark III + Canon EF 200mm f/2.0L IS USM, 1/1600, f2.0, ISO3200

After five years of photographing handball, the attraction has not faded. If anything, it has become quieter and more concentrated. The mechanics of the work no longer demand conscious attention: the camera, the settings, the exposure decisions all recede into the background, handled almost automatically through repetition and familiarity. This leaves space for something else. During a match, the work settles into a kind of flow, where technical choices happen without interruption and attention is directed almost entirely toward reading the game and waiting for the right image to surface. In that state, the task is no longer to operate the camera, but to remain present, patient, and receptive to recognise the moment when everything aligns on court.

Canon 1D X Mark III + Canon EF 200mm f/2.0L IS USM, 1/1600, f2.0, ISO3200

While movement defines handball, faces give it meaning. Emotion appears immediately and without mediation. Concentration, frustration, relief and hesitation are visible within moments, often written clearly across a player’s face. A technically precise image of action carries limited weight if it lacks this dimension, while a less perfect frame, made at the right emotional moment, can communicate far more. At this point, the boundary between sports photography and documentary work becomes blurry. The aim is no longer to document what happened, but to blend it with how it felt for those involved.

Canon 1D X Mark III + Sigma 105mm f/1.4 A, 1/1600, f1.4, ISO1250

Composition, too, reflects this reality. Handball courts are dense visual spaces where lines intersect, bodies overlap and clarity is rarely absolute. Clean, isolated forms are the exception. Rather than resisting this, it often makes sense to accept the visual congestion and work within it, using layers, partial obstructions and messy movement to document the physical pressure and pace of the game.

Handball exists slightly outside the main commercial spotlight of global sport, and this distance gives it a particular character. The moments feel less performative, less shaped for the camera. For the photographer, the proximity to the game is tangible: the sound of contact, communication, the rhythm of game, but also the momentary silence. When an image works, that closeness is present within it.

Canon 1D X Mark III + Canon EF 200mm f/2.0L IS USM, 1/1600, f2.0, ISO3200

In the end, handball photography is not defined by equipment or settings, even though both matter and demand precision. Shutter speed, aperture, autofocus and familiarity with the camera are necessary foundations, and without them the work quickly falls apart. But once they are in place, they recede into the background. It is about staying close, close enough to sense when something shifts, when a gesture, a look, or a pause briefly reveals more than the action itself. The photograph does not stop the game or explain it. It offers a fragment, shaped by my attention and timing, that reflects how the game was experienced by me in that moment. What keeps me returning is not the promise of spectacle, but the possibility that, somewhere between two actions, an image will emerge that feels true to the rhythm, the pressure, and the fleeting clarity of handball as it unfolds. I have yet to make a photograph that truly brings all of these elements together, that I would be really happy with, and it is this absence that keeps me sitting court-side.

All images taken 26.1.2026 at the Dicken - BK-46 Finnish Handball League game in Pirkkola, Helsinki, Finland.

Silence in the snow - reflections on winter nature and wildlife photography

There is something quietly instructive about spending a day in nature, especially when nothing dramatic happens. No rare species, no "perfect light", no "decisive moments" worthy of a field guide or a gallery wall. Just cold air, familiar, common birds, a slow walk, and time passing at what feels like a slower pace.

Common blackbird (Turdus merula). Canon R6 + Sigma 105mm f/1.4A. 1/800, f1.4, ISO400

I enjoy nature deeply, not as a spectacle, but more as a condition, as what it is. Being outside, especially among trees, birds, and, today, snow, induces a kind of mental deceleration, an internal slower pace. Psychologists might describe this as a reduction in cognitive load or a shift from directed attention to what is sometimes called “soft fascination.” Whatever the label, the experience is unmistakable each time I step into nature: irritating thoughts loosen their grip, breathing becomes easier, and each moment feels momentarily sufficient, just as it is. There are no expectations for each minute.

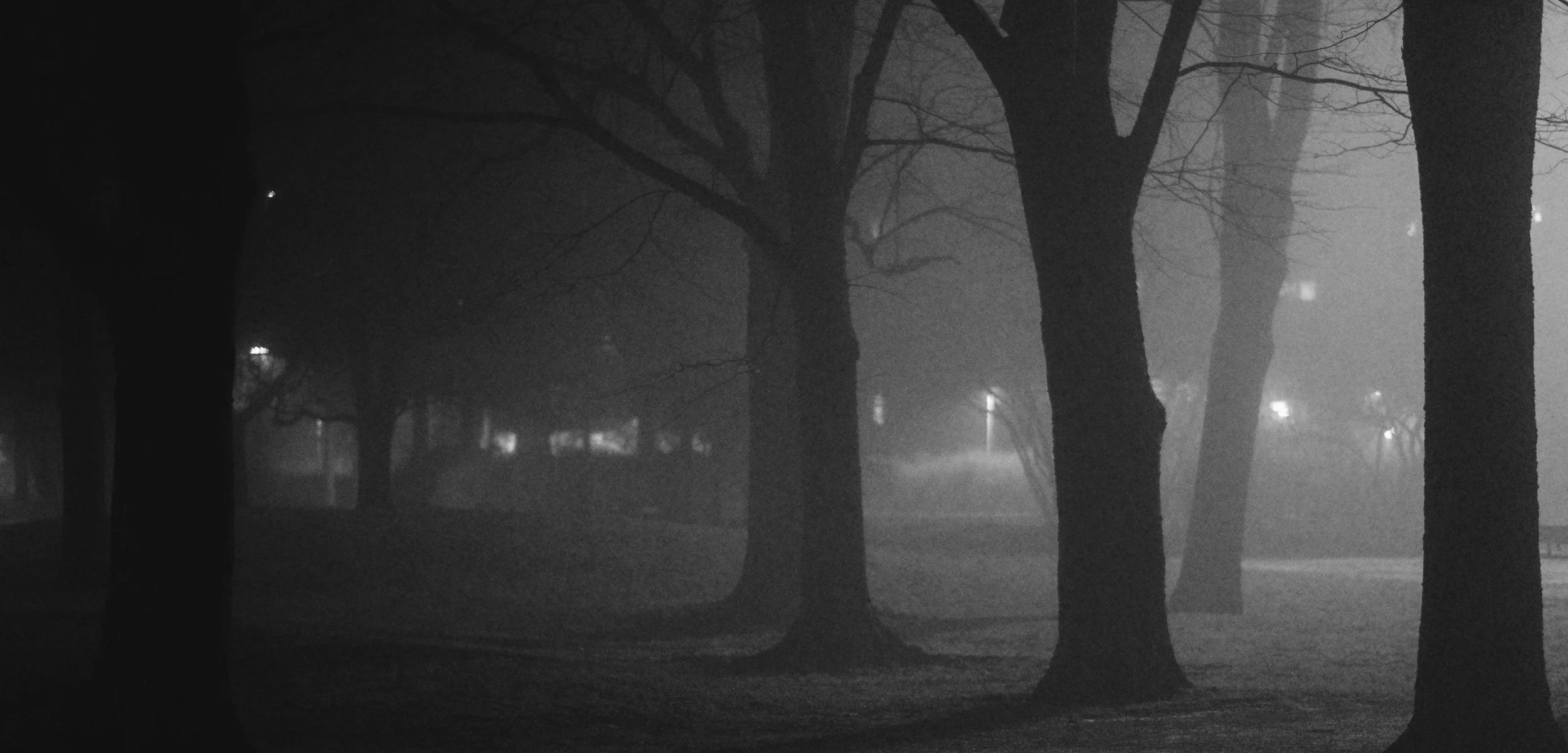

Winter day in Seurasaari, Helsinki, Finland. Canon R6 + Sigma 105mm f/1.4A. 1/250, f1.4, ISO200

Today, while visiting Seurasaari here in Helsinki, Finland, that effect was amplified. It was cold, around −8 °C, with a light snowfall. Snow has a peculiar acoustic property. It absorbs sound. In cold weather, especially during snowfall, the environment becomes hushed in a way that feels almost engineered. The absence of noise does not equal emptyness. It is full, dense, and strangely comforting. Walking through it feels less like moving through space and more like being embraced by it.

Snowfall in Seurasaari, Helsinki, Finland. Canon R6 + Sigma 105mm f/1.4A. 1/250, f1.4, ISO200

I am not a wildlife photography expert, and I don’t aspire to be one. My photos are not the result of rare access, or deep encyclopedic knowledge. Most of the time, I’m photographing everyday common birds and squirrels, species so familiar they are often overlooked, or not seen as interesting. And yet, trying to capture a good photograph of them is deeply satisfying. These birds and squirrels are quick, alert, inconsistent.

What draws me back is not the pursuit of technical perfection, but attention. I find myself choosing a few birds, or a squirrel, and simply following them or it for a while. Watching how it moves, where it pauses, how it reacts to my presence, or ignores it entirely. Over time, even these ordinary animals begin to feel distinct. Not in a sentimental way, I can't read their minds even if I try to, but in a behavioural one. Patterns emerge. Temperaments differ. There is personality, and that is were it becomes interesting. They might be common, and seen as boring, but much like with people, personalities are what make people different, and thus interesting.

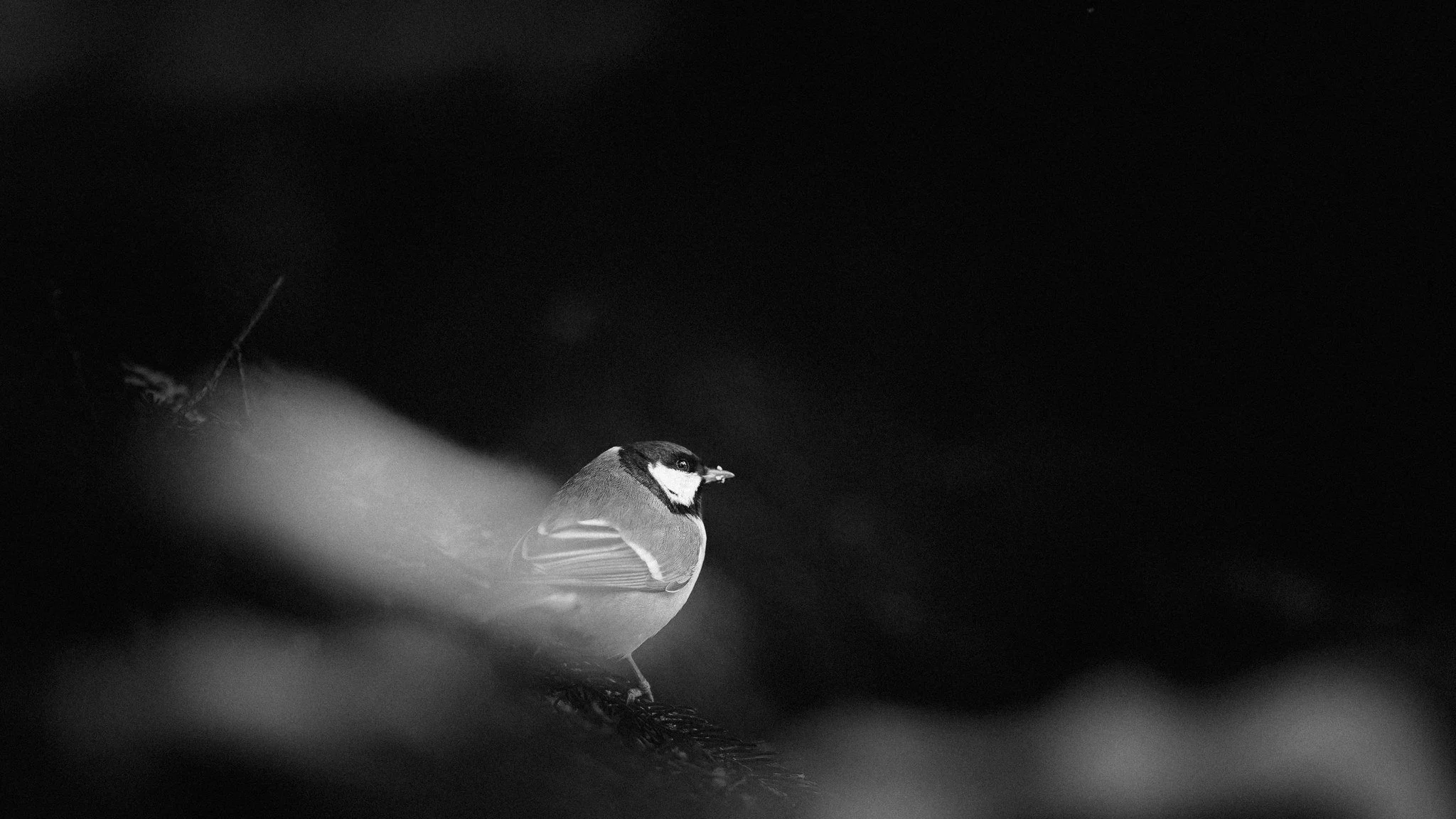

Great tit (Parus major) in Seurasaari, Helsinki, Finland. Canon R6 + Sigma 105mm f/1.4A. 1/400, f1.4, ISO400

I photograph these moments because they feel worth documenting. Not because they are exceptional, but because they are specific. This specific bird, with its personality, on this branch, in this light, on this cold, silent day. For me, that specificity carries meaning. It is a small act of witnessing, the moment existed, and I experienced it.

Common blackbird (Turdus merula). Canon R6 + Sigma 105mm f/1.4A. 1/400, f1.4, ISO400

In a world that rewards scale, speed, and spectacle, there is something quietly resistant about paying close attention to the small and the common. Nature, especially in winter, does not demand admiration. It simply continues. Being present with it, calm and unhurried, feels less like an escape and more like a return.

Red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris). Canon R6 + Sigma 105mm f/1.4A. 1/400, f1.4, ISO800

Hello world

For about ten, maybe fifteen years, I have had the intention of starting a blog on photography. And finally, here it is. Imagine the amount of procrastination I have been doing in the meantime. I don't know why I haven't started it earlier, maybe it has been about finding the right platform, the most suitable type, the perfect colour theme, or something similar. And I have to admit, now the timing is a bit off.

Lauttasaari - Drumsö | January 17, 2026. Canon R6 + Canon EF 50mm f/1.2L USM

The world has moved from Web 1.0 to 2.0. Social media and artificial intelligence now runs the world, and traditional blogs are more or less dead. Or are they? Well, I don't know, and to be honest, I don't care too much about it. For me, this blog is a way of reflecting and writing about my passion, photography. What photography is for me. Why I enjoy it so much. What it means to me. It is also a way for me to showcase what I find worth documenting and presenting.

Lauttasaari - Drumsö | January 17, 2026. Canon R6 + Canon EF 50mm f/1.2L USM

Most of the images in this blog will be in black and white. At least for now, maybe this will change in the future, who knows. At the moment, I find colours distracting. This does not mean all photographs I take are in black and white. Far from it, as can be seen in the different portfolios here, especially for sports photography. But for the last few years, I have been in the black and white phase. I will dive deeper into this at some point, as I find it interesting. Is it because of my partial colourblindness (red-green)? Or is it because of my mentality? My age?

Lauttasaari - Drumsö | January 17, 2026. Canon R6 + Canon EF 50mm f/1.2L USM

If there is anyone reading this, I hope you will enjoy the photographs, and the texts. I will try and write posts regularly.